Pronouncing Macao

Apparently it’s sometimes okay to pronounce foods differently.

- You say, “Tuh-MAY-toe.” I say, “Tuh-MAH-toe.”

- You say, “Puh-TAY-toe.” I say, “Puh-TAH-toe.”

- You say, “Kuh-KAY-oh.” I say, “Kuh-KAH-oh.”

But you shouldn’t do that with place names.

- You say, “Wah-KEESH-kah.” I say, “You’re wrong.”

And for the game in question, it’s just “Muh-KOW.”

Spelling Macao

By the way, Macao is now spelled M-A-C-A-U, unless you’re referring to the board game Macao.

In either case, this is a reference to a port city in China just west of Hong Kong.

Playing Macao

Macao ranks among the simplest-to-learn eurogames that I’ve ever played. It’s got plenty going on and plenty of options, but it’s really easy to pick up.

Part of the reason for this is that each step of a round is clearly spelled out on each player’s personal play mat. (Just ignore the misspelling – “activiated”.)

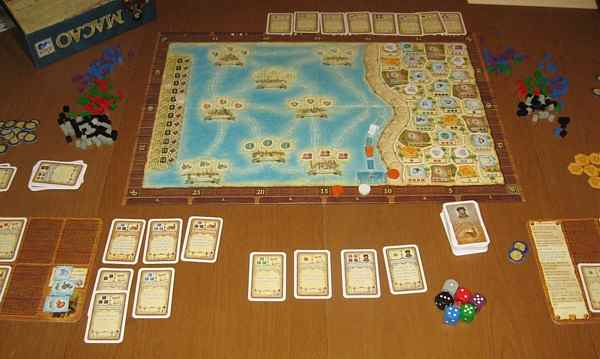

Macao has lots of tiny, colorful, wooden cubes to play with. They are used as building materials to “construct” office, building, and person cards that are randomly available each round.

There is also a set of colorful dice that match the colors of the cubes. These dice determine the colors and numbers of cubes you can place around your personal wind rose each turn.

Here’s how these three elements work together.

The dice are rolled. You can select two of them. If the purple die shows 5, you take 5 purple cubes and set them next to the 5 spot on your wind rose. If you also take the blue die showing 2, you put 2 blue cubes by the 2 spot on your wind rose.

It is this cube selection and placement that make Macao unique. The cards you build require specific combinations of cubes. The hitch is that you only have a certain group of cubes next to your wind rose available for spending each turn. You must plan ahead to get the right number and color combination of cubes in the same space next to your wind rose so that you can spend them as required on a card on your player mat.

Each round you rotate your 7-sided wind rose clockwise one “space”. An arrow points to the cubes you can spend that turn.

Winning Macao

As in so many games, the winner is the player with the most victory points. Being a game designed by Stephan Feld, there are lots of ways to get those points.

One of the main ways to get points in Macao is to turn cubes (via cards) into gold and spend the gold on points. The ratio of gold to points varies from round to round as determined by numbers on the bottom of the cards available each round.

Another chief source of points is shipping goods tiles to various ports. You can also use cubes to buy goods from one of the 30 “quarters” of the city. You spend additional cubes to move your ship from port to port. The first player to unload a type of good (at the port that wants it) gets 5 points. The 2nd gets 3, and the 3rd gets 2.

At the end of the game (12 rounds), you can get more points from your longest chain of purchase in the city (the 30 quarters) and from certain cards you have built that award bonus points.

Evaluating Macao

I like games with lots of cubes. (See El Grande.) I like games with lots of replay value. (See Agricola.) Macao has both.

In a single game of Macao, you only use about half the deck of building/person cards. This fact leads me to my one negative criticism of the game.

If one of the end game bonus points cards turns up late in the game, it may be worthless because no one prepared for it by collecting what it requires. How would you have known? If that same card shows up early in the game, you can take a chance on it, but you might regret it later if none (or very few) of the related cards show up – or they do, but someone else grabbed them ahead of you. (Note that you can also spend cubes to alter the turn order.)

Is Macao as good as El Grande or Agricola? Maybe not, but I’ll enjoy it for many dozens of plays to come. I think you might too.

Check the price of Macao on Amazon.

Pingback:Gaming Hoopla, Spring 2013 | My Very Own Corner of the Web